What is PocketBase?

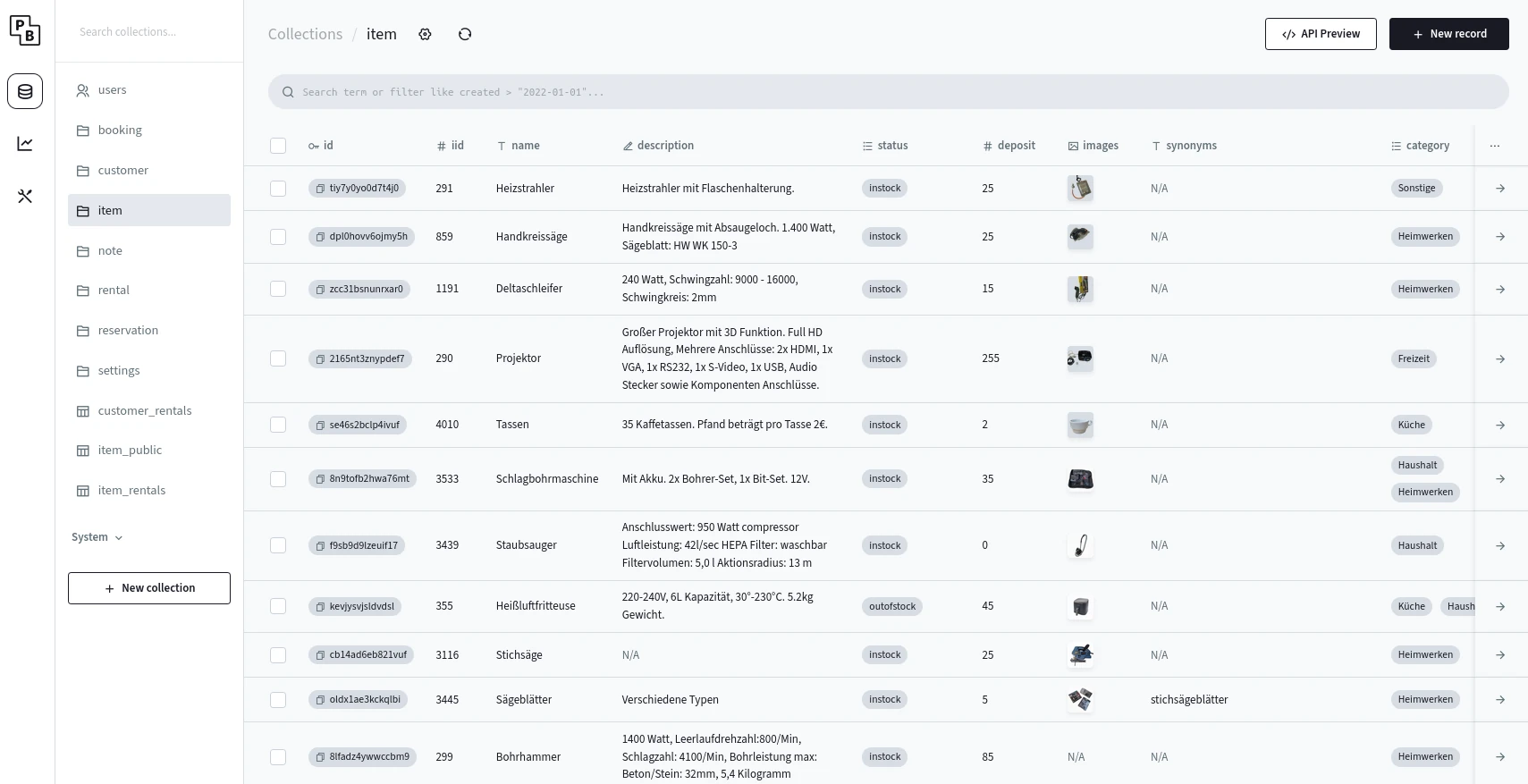

PocketBase is a self-hosted, open-source, “ready-to-use” backend for building (web) apps. Its purpose is to help developers get started much more quickly when prototyping new apps as it relieves them from the burden of having to build boilerplate functionality like authentication, authorization / RBAC / ABAC, file storage, realtime events, thumbnails, an admin dashboard, monitoring / analytics etc. Instead of having to reinvent the wheel (e.g. rolling yet another user management and login mechanism) for every new app, devs can instead focus in the actual business logic of their product. The underlying data schema (called collections) can be defined via an intuitive web UI editor while PocketBase takes care of mapping it to database tables and exposing according REST- and Websocket endpoints.

Quoting from their docs:

The basic idea is that the common functionality like crud, auth, files upload, auto TLS, etc. are handled out of the box, allowing you to focus on the UI and your actual app business requirements.

PocketBase is written in Go and extremely simple to get started with. The entire framework can be run as a single executable without any additional configuration, database setup, etc. It uses SQLite as a database under the hood, which – according to their FAQs – is way sufficient for the majority of applications (I can confirm that).

PocketBase, however, isn’t the first of its kind. Alternatives include Supabase (TypeScript), TrailBase (Rust), Frappe (Python) and also tools like Hasura to some extent, all of which, in turn, are open-source alternatives to proprietary backend-as-a-service (BaaS) offerings like Firebase. Without having tried all of them, I’d still argue that PocketBase is probably easiest to use though.

Extending PocketBase with custom code

While PocketBase can do a lot of things right out of the box without writing any code (arguebaly its a low code framework to an extent), you’ll still soon get to a point where some small pieces of custom logic are needed. For example, you might want to roll custom validation logic (check attribute A in collection X to match some property of the incoming request), implement scheduled jobs like nightly cleanups or expose custom tailored web endpoints.

To extend PocketBase with own code, you’re essentially given two alternatives: either use the Go SDK to actually extend PocketBase or use the JavaScript SDK to write code that is executed dynamically at runtime (in JSVM, powered by the pure-Go JS runtime goja).

These two approaches differ quite fundamentally. With the first one, you actually build (compile) your own application binary with code that includes PocketBase as a library / framework (Go doesn’t have a “plugin”-system where you could load code dynamically at runtime like in Java or any interpreted language). The second approach keeps using PocketBase “stand-alone” (run the pre-built binary) and custom JavaScript code is loaded (from a directory called pb_hooks/) and interpreted on the fly. That is, PocketBase can effectively be used either as a framework or as a runtime, in some sense.

There are pros and cons to both. Using the Go SDK does, unsurprisingly, result in better performance (even though it doesn’t really matter much for the vast majority of apps) and you get proper compile-time type-checking, syntax highlighting, etc. On the other hand, the JavaScript approach comes with less overhead (no Go tooling and no compile step needed) and is probably the more beginner-friendly language. But: you’ll have to deal with “magic” global objects and functions, which you’ll rarely get autocompletion, etc. for in your IDE.

Proposed code structure for pb_hooks

While building leihbackend I opted for the second approach, i.e. chose to go with runtime-evaluated JavaScript code for custom logic. Main reason for this choice was the fact that my other fellow volunteers, who’d potentially want to contribute to the project too, would be more familiar with writing JS than with having to deep-dive into Go (on the other hand, as AI-assisted coding came along, a Go codebase wouldn’t be as much of an entry-barrier anymore after all).

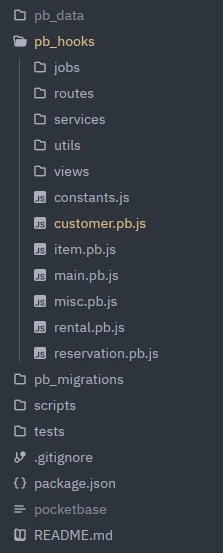

I found the following project structure to be very handy:

All pb_* directories are prescribed by PocketBase’ naming convention. pb_data is where all application data (SQLite database, file uploads and backups) are stored (thus excluded from Git), pb_migrations is where the (JavaScript-based) schema- / database migrations are stored (these are usually generated automatically when modifying the data schema via the UI editor) and pb_hooks is the real interesting part – this is where all custom code lives.

PocketBase will automatically load all files named *.pb.js inside pb_hooks. These files, in turn, can arbitrarily import other files. While having a handful of JS files stored “flat”” under pb_hooks is totally sufficient for moderately large applications, things become messy the more custom logic you need.

This is why I decided to split my code along two dimensions: on the first axis, my hooks are organized by function and, within each function package (explained below), there’s one file per entity type (i.e. per collection, e.g. customer, product, etc.).

Top-level entrypoints

All “top-level” files stored directly under the hooks dir are the “entrypoints”, as these are being loaded when PocketBase boots up. They’re mostly only responsible for importing other files as part of different event hooks.

To give an example:

1 | // customer.pb.js |

There is one file for each database entity. In case of leihbackend, these are customer, item, reservation and rental. Besides, there is main.pb.js for “globally” relevant things (primarily onBootstrap() code that shall run once initially during startup) and misc.pb.js which contains everything that doesn’t really fit anywhere specifically.

The routes package

This is where custom HTTP endpoints are defined. E.g. leihbackend features an endpoint to export items as CSV, which is defined at routes/item.js. This corresponds more or less to the “view” layer in a classic MVC architecture, while “view” means REST endpoint here.

The services package

This is where all core business logic lives, including data validation rules, aggregation functions, custom getters / setters implemented as static util methods, etc. This package is being used by most of the other packages. For example, while the custom CSV export endpoint from above is defined inside the routes package, its actual “core” implementation lives in a service. To give an idea of what I consider part of the services, exemplary functions inside this package include getDueRentals(), exportCsv(), validateItemStatus(), sendCustomerWelcomeMail(), etc.

The jobs package

This package contains the implementation of all scheduled jobs, e.g. routines to delete inactive customers in a batch-wise fashion. It usually imports methods from services and is imported from inside a cronAdd() function in the top-level package.

The utils package

The utils package is home to static utility functions like fortmatHumanDateTime(), arrayUniqueBy(), wrapInTransaction() or the like. They exist stand-alone and don’t have any dependencies.

The views package

While the name might be confusing after I introduced the routes package as the equivalent to an MVC-app’s view layer, this is where custom HTML templates live (a more appropriate name would probably be templates). While PocketBase usually constitutes the backend part of a single-page- or mobile app, you can, technically, also render HTML templates. While I’d advice against delivering static HTML from PocketBase extensively, it comes in handy for small things like displaying a simple “User account confirmed.” page upon clicking an e-mail verification link or such. Also, the views package is where I decided to place plain-text- and HTML templates for e-mails sent by the backend.

Conclusion

The above presented “architecture” (actually, it’s rather just a proposed folder structure) is what turned out to work very well for me while working with JavaScript-based hooks in PocketBase. I’m sure there is room for improvements, but for now, this is what I’d recommend when using PocketBase for an application that goes beyond the built-in CRUD functionality.

Besides that, I’d briefly like to take the chance to express my excitement about PocketBase – it’s such a convenient and easy-to-use, yet powerful tool for building backends and I chose it as my new default way to go for new apps. Thanks a lot to the developers! I’m looking forward to see how the project is going to evolve in the future 🙏.

If you’re having questions or comments, feel free to post time. I’m curious to know what you think about my project structure proposal and about working with PocketBase in general.

Comments