👉 Update (10/2025): Today, a much more straightforward way to set up DNT-over-TLS on a Linux machine is to simply use the built-in DoT capabilities of systemd-resolved, see here. You might use the resolvers provided by dnsforge, dnscry.pt, dns0 or any other. As an alternative, some peole (including myself) also prefer DNSCrypt over DoT, which is not natively supported by systemd, though.

Privacy on the Web

Luckily, most traffic on the web is encrypted today, which means nobody between your computer and the web server knows what you are sending or receiving. This includes your internet service provider (ISP), any kind of government agency or a potential attacker on your network. Since the entire HTTP packet, including its headers, is encrypted, they will not even see what website you are visiting. At least not for sure. What they can see is the target web server’s IP address from the IP packet’s header. However, there might be several different web servers for different web sites listening on that IP and there is no chance to find out which one you intended to visit.

The Problem with DNS

However, although HTTP is usually encrypted, DNS is usually not. So before your browser performs the actual HTTP request, your operating system will perform a DNS query to resolve, for instance, “google.com” to 216.58.207.46. Your question – “What’s the IP for google.com?” – is contained in the DNS query as plain text, so everyone between your computer and the DNS server will know that you are trying to access Google – or whatever website. And, of course, the provider of your DNS server will know as well, since it has to answer the query.

Usually, your default DNS server is the one provided by your ISP. And since the ISP can directly associate your internet connection with your name and address it will know about any website that you – as a person – visit. Even if you change the default to something else (e.g. Google’s public DNS resolver 8.8.8.8 or CloudFlare’s 1.1.1.1), your ISP can still read your DNS queries as they mandatorily pass through its network. Consequently, in order to browse more privately on the web – in addition to using HTTPS - there are two steps you need to consider:

- Change your DNS provider to one that is more anonymous and does not have personal information about you

- Encrypt your DNS queries to prevent anyone in the middle (especially your ISP) from reading them

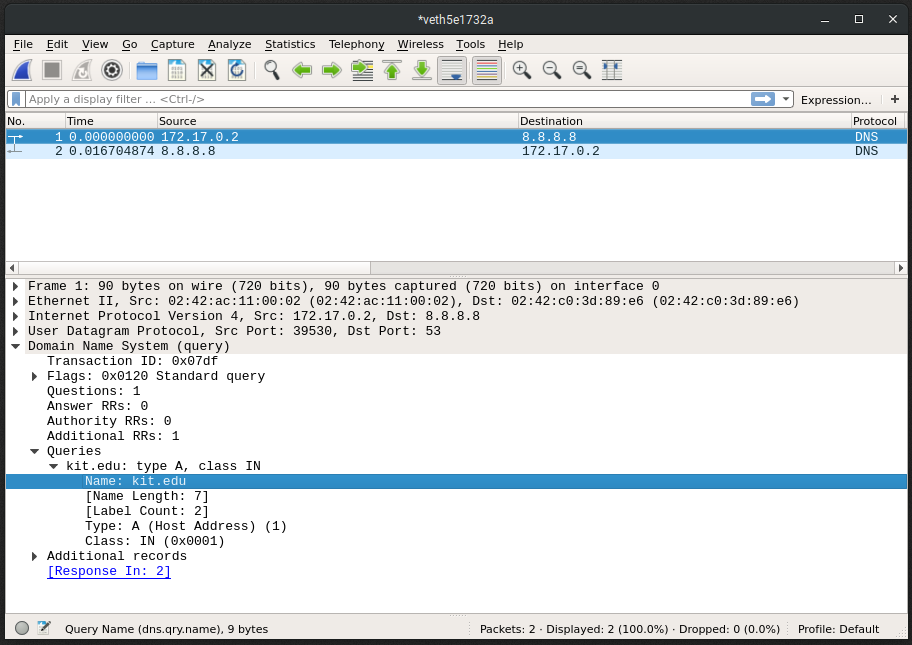

Example of a non-encrypted DNS request for kit.edu to Google’s 8.8.8.8 DNS resolver

Luckily, the DNS-over-TLS specification already provides a solution and it is already supported by the three largest public DNS providers CloudFlare, Google and Quad9. You only have to configure your computer to use it.

CoreDNS Setup

In this article, I show you how to use DNS-over-TLS with CoreDNS as a local DNS recursor on your machine. It is an open-source software and primarily known for being used as a nameserver in Kubernetes networks. Please note that I decided to use CoreDNS, because it is particularly easy to configure and offers a variety of cool plugins, like metrics collection with Prometheus and more. However, Ubuntu’s default DNS recursor systemd-resolved apparently supports DNS-over-TLS as well and is probably easier to get started with initially. So if you prefer to go the easy way, just head over to the previously mentioned blog post and follow its instructions.

Disclaimer: Please use this guide at your own risk. I do not take any responsibility in case you accidentally crash your DNS setup.

In order to set up CoreDNS, there are a few steps to follow.

- Download CoreDNS from the website, unpack the binary to

/usr/local/binand make it executable (sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/coredns) - Install

resolvconfas a tool to manually manage/etc/resolv.conf:sudo apt install resolvconf - Set

dns=defaultin/etc/NetworkManager/NetworkManager.conf - Add

nameserver 127.0.0.1to/etc/resolvconf/resolv.conf.d/head - Create

/etc/coredns/Corefileand paste the configuration shown below. In this example, we are using CloudFlare as a DNS provider. You can use Google or Quad9 as well, just change the IPs. - Create a new user for CoreDNS:

sudo useradd -d /var/lib/coredns -m coredns - Set some permissions:

sudo chown coredns:coredns /opt/coredns - Download the SystemD service unit file from coredns/coredns to

/etc/systemd/system/coredns.service - Disable SystemD’s default DNS server:

sudo systemctl stop systemd-resolved && sudo systemctl disable systemd-resolved - Please Note: From that moment on, you will not be able to resolve any web pages anymore, unless you enable DNS again

- Enable and start CoreDNS:

sudo systemctl enable coredns && sudo systemctl start coredns - You should be able to resolve domain names, again. E.g. try

dig +short kit.edu. If an IP address is printed, everything works fine.

1 | # /etc/coredns/Corefile |

Example of an encrypted DNS request for kit.edu to CloudFlare’s 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver

Alternatively, use the following forward statement to use the independent BlahDNS instead of CloudFlare as provider.

1 | forward . tls://2a01:4f8:1c1c:6b4b::1 tls://159.69.198.101 { |

What happens?

Let us examine what happens (in terms of DNS) when you type “kit.edu” in your browser’s address bar and hit enter.

- Your browser asks your operating system to resolve

kit.edu - Your OS finds out that its primary configured nameserver is

127.0.0.1:53, i.e. your local CoreDNS, and consults that one - CoreDNS checks its cache and in case of a miss consults its configured nameserver at

1.1.1.1, i.e. CloudFlare - CloudFlare, again, checks its cache and in case of a miss goes up the hierarchical chain of nameservers until one of them has an answer

- Eventually, your browser performs

GET / HTTP/2.0to129.13.40.10withHost: kit.edu

Further Reading

Here are a few additional posts about DNS, which I found very useful.

Please let me know if my guide is missing any required steps. Good luck, have fun and browse safely!

Comments